There seems to be no respite for the ringgit: it lost 6% in the past month, it has been dubbed among one of the worst performing emerging Asian currencies, and it has lost the confidence of investors.

Just last Thursday, the Malaysian currency traded at 4.4707 to the US dollar, flirting with levels not seen since the depths of the Asian financial crisis more than 18 years ago.

Also, the ringgit is expected to suffer its fourth consecutive annual loss against the US dollar this year, despite efforts by Bank Negara Malaysia to stem the currency’s slide, leaving investors to ponder if they will see a repeat of 1998.

The central bank has reiterated that it would not tighten controls on the flow of funds across its borders and that the stepping in was to “maintain orderliness”. Its recent move was a crackdown on trading in the non-deliverable forwards market.

Non-deliverable forwards (NDF) is an offshore, liquid market where investors exchange a certain currency for another because of restrictions in the domestic or onshore market.For example, if Investor A wants to exchange ringgit for US dollar but does not want to be confined to BNM rules, which governs forex trading in Malaysia (the domestic market), he will trade in Singapore or Hong Kong.

Source: Reuters

BNM then rolled out another policy on Friday which took a more export-friendly approach and at writing time, the ringgit has slightly stabilised.

“Still, the ringgit’s long-term outlook remains uncertain,” said analysts for Credit Suisse, echoing sentiments of volatility and more aggressive measures by the central bank.

So, the question we all ask is, will Malaysia see a repeat of 1998.

A resurgence of capital controls?

To recap, the ringgit plunged to a record 4.885 per dollar in 1998, leading then-prime minister Tun Dr Mahathir Mohamad to impose restrictions, including a peg at 3.80 per dollar and a ban on offshore trading in the currency.

He also blamed US billionaire George Soros and other “rogue speculators”; the peg was eventually scrapped in 2005.

“I don’t see this as likely,” said Nurhisham Hussein, head of economics and capital markets of the Employees Provident Fund.

Speaking to iMoney on the possibility of a 1998 parallel, he said Malaysia is a major commodity exporter and the country needed to have a flexible exchange rate to buffer domestic revenue from changes in global commodity market prices.

“Using capital controls to stabilise the ringgit exchange rate would be counterproductive, as we will be trading off currency volatility against Malaysian jobs and corporate solvency. Stamping down on currency volatility just transfers that volatility to Malaysian companies and workers,” he said.

Wan Imran Chik, a former international relations officer to a prominent politician and a critic of government fiscal policies, said what BNM viewed as a move to “speculate” against the ringgit was actually a move by investors to hedge against loses from the tumbling ringgit.

“BNM’s actions has ‘scared’ a lot of foreign investors and fund managers of the very possibility of capital controls, so such action is deemed as a step towards that direction.”

He told iMoney the consequences of reintroducing capital controls would have dire effects on the country, politically and economically.

It would not go well with foreign investors as that would be deemed a failure in economic management, he said, adding that once such a reputation is established, it would take a very long time to recover and restore the confidence of investors.

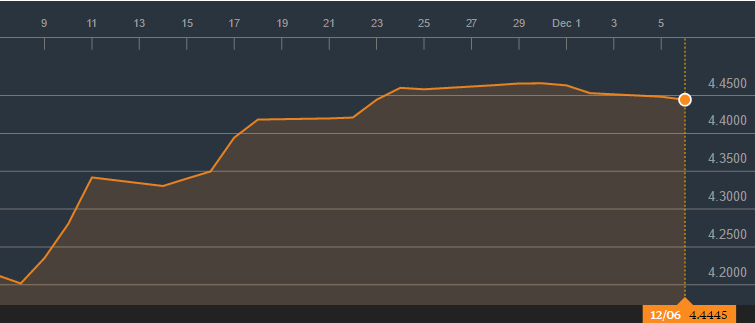

The ringgit’s performance against the US dollar over the past month.

Chart courtesy of Bloomberg.

Stemming volatility

The ringgit, as well as the Indonesian rupiah, are among the favourites of global investors, making them Southeast Asia’s most volatile currencies.

Overseas ownership of Malaysian debt has climbed four times over in the past decade to 36%. Foreign ownership of the country’s bonds is one of the highest among five Asian economies tracked by the Manila-based Asian Development Bank.

That might seem like a vote of confidence but it is less desirable in times of financial-market stress, as evidence by the election of Donald Trump as US president.

“There’s no way to fully insulate ourselves from these, while still trying to be open to the rest of the world,” said Nurhisham.

“I think we need a deeper and broader onshore market. But the kind of currency volatility we have seen is largely due to the unusual uncertainty surrounding major geopolitical events.”

Is the ringgit the worst performing currency in Asia?

Actually, the Turkish lira has been the worst performing currency in Asia this year, not the ringgit. If we are looking at East Asia specifically, the Filipino peso has performed the worst on a YTD basis, while for November, it’s the Japanese yen. This is indicative of what’s going on – a general sell-off in the rest of the world relative to the US dollar. The ringgit is hardly alone, though it has been hit harder than most.

Nurhisham Hussein said in an email to iMoney.

Political instability and oil prices are the main reasons the ringgit is volatile, said Adrian Koay, a dealer with UOB Kay Hian.

According to reports, the ringgit has been under pressure tracking feeble global crude prices and political tensions that has brewed since reports surfaced of an alleged scandal around state investment vehicle 1Malaysia Development Berhad, which is linked to Prime Minister Datuk Seri Najib Razak.

“Oil prices are hard to control, but if we worked on our country’s political issues, this will definitely bring more stability to the ringgit”, Koay told iMoney. (A counterargument to political risk and its effect on the ringgit can be read here.)

Tighter belts and ‘Cuti-cuti Malaysia’

The ringgit slide comes on the backdrop of higher living costs and soaring house prices that have left Malaysians struggling to meet the demands of daily life. Even vehicle sales took a dive in October, citing tepid consumer sentiment and a weak ringgit.

If the ringgit reaches new lows, imports and locally processed or manufactured products which rely on imported raw materials could rise, Wan Imran told iMoney.

“For example, Malaysia imports tons of wheat which is processed locally into flour and used by local food manufacturing companies to make bread. Malaysia also imports a lot of milk and dairy.

“We could see a rise in these products, so an increase in our living cost for daily consumption,” he said.

Follow these saving tips when it comes to food:

- Buy more vegetables, less meat.

- Stock up on GST-exempt items.

- Pack lunches and prepare meals in advance.

- Create a grocery list in advance to minimise what you spend on food.

- Buy snacks in bulk.

- Avoid upgrades in restaurant meals.

- Cook in bulk and save leftovers for a day or two and have them for lunch or breakfast.

Nurhisham however provides a different picture. Based on research, he said one unusual finding over the last couple of years is that despite the ringgit’s sharp depreciation against the US dollar, it has had almost no effect on imported inflation.

“For most of 2014 to 2015, overall imported inflation outside was actually negative, while food inflation has been steady before and after the ringgit started falling.”

For the most part, the effect on Malaysians will be minimal unless they are travelling to the US or to countries within the US dollar bloc such as Hong Kong, he said, adding that there’s not much need to take precautions unless a person has dollar liabilities such as children schooling in the US.

To cushion volatility, turn to foreign currency current accounts. It allows you to keep foreign currency for future use and at the same time hedge against foreign currency fluctuation.

“We may just have to tighten our belts even further and, sadly, maybe even cancel any plans for trips or holidays abroad where the currency is much higher, or put such plans on hold and just settle for ‘Cuti-Cuti Malaysia’,” Wan Imran said.

Can’t go abroad for a vacation? Fret not, Malaysia has ringgit-friendly destinations that can give you that very same experience locally, with destinations ranging from nearby Kuala Kubu Bharu to Kundasang in Sabah.

And as for investors, their best bet is to diversify. “You can always move assets into different currencies. The more you diversify, the lesser risk you take,” said Koay.

And the future of the ringgit?

The ringgit’s steep decline against the US dollar started in September 2014, shedding 10.8% to end at 3.495 against the US dollar as at end-2014.

Until mid-2005, the ringgit was pegged at RM3.80 against the US dollar. Only after the US Federal Reserve launched the first round of quantitative easing at the beginning of the global financial crisis in 2008 did the ringgit start to depreciate.

Against the US dollar, it went from RM2.50 to more than RM4 within a year from July 1997. Prior to 1998, when the ringgit was still an international legal tender, Malaysians could easily hedge the exposure.

However, after September 2, 1998, when capital controls were imposed, the movement of the ringgit was restricted.

And it was only after Bank Negara relaxed the restrictions that local banks started offering some hedging mechanisms.

So with such an unpredictable track record, what do we make of the near future?

It will be bleak, around RM4.75 to RM4.80 against the dollar, unless the Malaysian government replenishes or top up foreign exchange reserves, said Wan Imran.

Nurhisham predicts this is a one-off market adjustment as global investors were taken off guard by the Trump election.

“As a result, most currencies including the ringgit will remain under pressure for the next month or so, especially with the Federal Reserve due to raise its policy rate in the middle of December.

“After that, and especially after President Trump officially takes over on January 20, I’d expect to see some reversal of capital flows to take place, as there’s no question that the markets have overreacted,” he said.